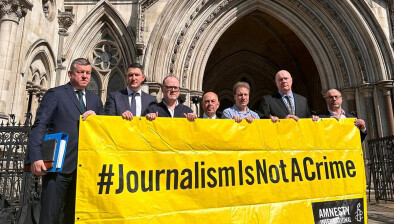

NI: Court of Appeal: Hearing to obtain search warrants against journalists fell ‘woefully short’ of required standard

The conduct of ex parte hearings where the PSNI obtained warrants in respect of the investigation into the theft of documents from the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland relating to the 1994 Loughinisland massacre fell “woefully short” of a fair hearing, the Court of Appeal has held.

About this case:

- Citation:[2020] NICA 35

- Judgment:

- Court:Court of Appeal

- Judge:Sir Declan Morgan

The Lord Chief Justice, Sir Declan Morgan, sitting with Lord Justice Seamus Treacy and Mrs Justice Siobhan Keegan, quashed the warrants authorising the search of the homes of journalists Barry McCaffrey and Trevor Birney and their business premises.

Background

In 2012, the families of six men murdered by the UVF in Loughinisland sought the production of a documentary. Mr McCaffrey established that an SDLP councillor had received a letter identifying the persons allegedly responsible. It was decided that the documentary would name the suspects. Mr McCaffrey indicated to a senior officer in the PSNI that the production team had concluded there was no risk to any of the three suspects as their names had been in the public domain since 1995 but that they would not name a further person, a police informant. The PSNI took no action to prevent the naming of the suspects.

The police ombudsman Dr Michael Maguire and some of his staff were shown the documentary at a private screening in 2017. It was identified that the production team had acquired sensitive documents relating to its investigation. In the film Mr McCaffrey said he received the material from an anonymous source.

On 8 August 2018, the PNSI and Durham Constabulary sought warrants in the County Court, seeking journalistic material consisting of all broadcast material together with unedited and un-broadcast footage relating to the documentary. Counsel for the PSNI drew the judge’s attention to the fact that there was an inter partes process for the obtaining of such information under the Police and Criminal Evidence (Northern Ireland) Order 1989. He did not, however, discuss its terms and conditions in any detail. Judge Rafferty QC granted the warrants.

Court of Appeal

Fine Point Films, the production company, its CEO Mr Birney, and Mr McCaffey sought orders quashing the warrants authorising the search of their homes and business premises in connection with the investigation of offences of theft, handling stolen goods, unlawful disclosure of information entrusted in confidence and unlawfully obtaining personal data.

The protection for journalistic sources was introduced by section 10 of the Contempt of Court Act 1981 which provides that no court may require a person to disclose the source of information contained in a publication for which he is responsible, unless that disclosure is necessary in the interests of justice or national security or for the prevention of disorder or crime.

The Court referred to cases on journalists’ Article 10 ECHR rights to freedom of expression. The judges referred to Goodwin v United Kingdom (1996) 22 EHRR 123, in which a journalist had been fined £5,000 for contempt of court in refusing to disclose the source of sensitive information regarding the financial status of a company. This was upheld by the House of Lords but the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) concluded that there had been a violation of the journalist’s Article 10 rights. The courts also cited Roeman and Schmidt v Luxembourg (2003) ECtHR 51772/99, where an investigating judge issued warrants for searches of the home and the offices of the newspaper of a journalist who had reported how a government minister had been fined for tax fraud. The ECtHR held that this was a violation of the journalist’s Article 10 rights, and it noted in particular the intrusive nature of a search warrant.

The Court of Appeal, citing R (Faisaltex Ltd) v Crown Court at Preston [2009] 1 WLR 1687, noted that the jurisprudence has frequently emphasised that search warrants confer a “draconian power”. In R (Mercury Tax Group) v Revenue and Customs [2009] STC 743, search warrants were described as a “nuclear weapon” which, unless properly justified, involve a gross infringement of civil liberties: “It does not perhaps need the use of such hyperbolic language to emphasise they should only be sought as a last resort and should not be employed where other less draconian powers can achieve the relevant objective.”

Sir Declan said the PSNI’s justification appeared to rely solely upon the fact that Mr McCaffrey, “a person of good character”, had declined to voluntarily provide the Metropolitan Police Service with material about a source in an earlier investigation. He had, however, responded expeditiously to the request through his solicitors and indicated that he was relying upon the Code of Practice of the National Union of Journalists (NUJ), which places an obligation on journalists to protect their sources.

The court referred to email traffic obtained by the PSNI warrants, in which there was discussion by Mr Birney and Mr McCaffrey about the risk of steps being taken by the police to try to establish the source of the leak: “Unsurprisingly both of them were anxious to ensure that they should take all steps to try to protect the identity of the source including the deletion of material.” The Court said there was nothing suspicious or inappropriate about this, as it is “exactly what one would expect a careful, professional investigative journalist to do in anticipation of any attempt to identify a source. It does not lead to any inference that such a journalist would commit a contempt of court.”

Conclusion

The Court of Appeal said that a fundamental principle of any ex parte hearing is that it should be fair, particularly where it significantly impacts the private and family lives of those affected: “No matter how sensitively done the unannounced arrival of several police vehicles and 7 or 8 uniformed officers exercising the power to enter and search one’s home while young children were wakening up preparing for school and guests were bemused to see their host being arrested constituted such an intrusion.”

There is a duty on moving parties in ex parte proceedings to take all reasonable steps to ensure that the proceedings are fair. In discharging that duty, they must, as put by Lord Justice Anthony Hughes in In Re Stanford International Bank Ltd [2010] EWCA Civ 137, “put on a defence hat and ask, what, if he were representing the defendant or a third party with a relevant interest, he would be saying to the judge. The applicant must, of course, then proceed to tell the judge what those matters are. It is against that standard that we have reviewed the conduct of the application and hearing in this case.”

The Court found that the conduct of the hearing for the search warrant “fell woefully short of the standard required to ensure that the hearing was fair”. The warrant was quashed.