NI: Alison Cassidy: Proposed personal discount rate will needlessly drive up claims costs

Alison Cassidy

Alison Cassidy, partner at BLM in Belfast, examines proposals to slash the personal injury discount rate in Northern Ireland.

The Minister for Justice in Northern Ireland, Naomi Long MLA, has asked officials to undertake a statutory consultation with the Government Actuary and the Department of Finance on a proposal to change the discount rate, which still stands at 2.5 per cent, to minus 1.75 per cent.

In an announcement by the Department of Justice, the Minister had come to the decision “having considered the discount rate, in particular, the significant decline in returns on investment since the rate was last set in 2001 and the need to ensure claimants are properly compensated”.

While we welcome the fact that the Department of Justice is considering setting a new personal injury discount rate (PIDR) for use in claims in Northern Ireland, we argue that doing so using the dated and discredited approach of the Damages Act 1996 is entirely misplaced and would needlessly drive up claims costs.

The power for Ministers to set a PIDR was first set out in the 1996 Act, which originally covered the UK as a whole. Since then, the power has been devolved separately to Ministers in Edinburgh and Belfast, although the current +2.5 per cent PIDR in NI was in fact set by Westminster (in 2001) before the reassignment of those powers.

The legislative landscape and the applicable PIDRs in England & Wales and Scotland have changed significantly since 1996 & 2001. Just last summer, new PIDRs were set under new legislation which in each case - Acts from 2018 and 2019 respectively - replaced the 1996 Act’s ultra-low risk approach to claimant/pursuer investment of damages.

In different ways, both new Acts set out more realistic approaches to assessing investment risk and returns and both allow for evidence-based adjustments for matters such as inflation, taxation and investment advice rather than reflecting the ‘broad brush’ approach adopted under the 1996 Act.

In our view, the 2018 and 2019 Acts were a reaction against the decision in February 2017 of then-Lord Chancellor Liz Truss MP to review the English PIDR using the 1996 Act. That process resulted in a PIDR of negative 0.75 per cent in England (and in Scotland not long afterwards) - an overnight reduction of over 300 basis points - which lead to dramatic increases in claims awards and to upwards pressures on insurance and reinsurance premiums for motorists and businesses. There were similar effects in clinical negligence cases resulting from NHS treatment for which the state is financially responsible.

The level of political concern at that rate was evidenced by the close interest of the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the days that followed the rate-setting decision and by a consultation about re-setting the PIDR beginning in March 2017 - almost immediately after the negative 0.75 per cent rate had been set. Unsurprisingly, the key goal of that consultation was to change the ultra-low risk approach associated with the PIDR.

In the absence of new legislation for NI, the Department contends that it is constrained by the 1996 Act to follow the ultra-low risk approach. However, in our view so doing would inevitably lead to NI consumers, business and their insurers, as well as Health Trusts and other claims handling public authorities in NI, experiencing even more significant financial effects than were seen in the rest of the UK in 2017.

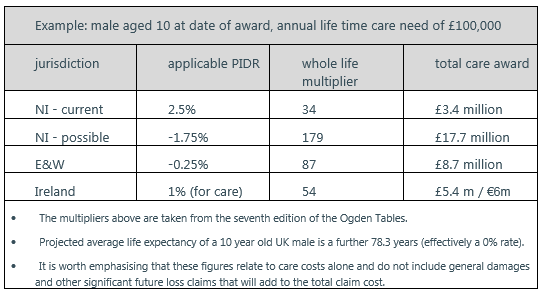

The hypothetical case of a 10 year-old sustaining injuries and requiring annual care costing £100,000 serves as an example for the purposes of comparison. The data in the table below shows that at -1.75 per cent, Northern Ireland would easily become the most expensive jurisdiction in the UK and Ireland by a sizeable margin. Some awards would, for no obviously discernible economic reasons, be more double than those in England & Wales and three times those in the Republic.

Driving up cost in this way will inevitably impact on the ability of NI motorists to access affordable insurance and on the competitiveness of NI businesses as premiums rise and some insurers could cease underwriting in the local market. In addition, the proposed rate would impose a significant burden on government funding as the cost of claims for which the state is responsible would substantially rise. Of particular concern is the effect on already-struggling local health trusts as the costs of clinical negligence claims soar. These sorts of outcomes not only seem deeply unattractive to us but may also be entirely unnecessary.

The 1996 Act permits courts to adopt a different PIDR to that prescribed by Ministers if it would be “more appropriate” to do so. The PIDR currently in place in England & Wales, negative 0.25 per cent, was set following detailed and painstaking analysis by the Government Actuary of investment risk and performance. In addition, it includes a significant margin of protection against under-compensation applied by the Lord Chancellor. Why shouldn’t this rate regarded as a “more appropriate” PIDR rate for use in cases in Northern Ireland when compared to an ultra-conservative PIDR of the order of negative 1.75 per cent with all the attendant negative consequences?

On a wider front, consumers in Northern Ireland are already burdened with the highest motor premiums in the UK. This difference across the UK’s constituent jurisdictions is likely to continue due to the following factors:

- General damages in NI were increased by, on average, 20 per cent in February 2019, further extending the gulf in valuations of injuries between the jurisdictions. As an example, the E&W 2019 guidelines assess a back injury where recovery takes place within 2–5 years at up to £9,970, whereas in Northern Ireland, for the same injury the JSB guidelines assessment is up to £30,000.

- Whiplash reforms will be introduced in E&W later this year and are expected to contribute to a significant decrease in awards and legal costs for these cases. Northern Ireland is excluded from the proposals.

- Small claims in NI which include personal injury are excluded from excluded from the small claims court track, unlike in E&W. This means that even in the most modest cases for vehicle damage and minor injuries defendants and insurers are paying significant legal costs.

- Pre-action protocols in NI are voluntary and impose no cost penalty for non-compliance (in the county court) meaning there is nothing to prevent cost-building activities and/or issuing proceedings prematurely. There are effective sanctions for this sort of behaviour in similar protocols in E&W.

What happens next?

The Minister has asked officials to undertake a “statutory consultation” and under the 1996 Act and this will very probably be a closed consultation, with no opportunity for interested stakeholders to get involved. We are informed that the Department will “provide a further update” on completion of the statutory consultation, but there is no indication whatsoever as to the likely time scale.

After this process, the Minister will “in due course” (here again no commitment on timing) give consideration to reviewing how the rate in Northern Ireland is set, which should will involve the introduction of new primary legislation. Given the backlog which Stormont is already facing it might take at least 18 months for such legislation to pass.

- Alison Cassidy is a partner at BLM in Belfast.