Christina Watts: RMS Titanic – putting the IP in shIP

Christina Watts marks the 113th anniversary this week of the sinking of RMS Titanic by exploring how intellectual property (IP) helped to shape the legendary vessel’s story.

I recently had the opportunity to visit the Titanic Wales Exhibition and found myself being filled with a mixture of curiosity and solemnity as I checked in and made my way to the exhibition room.

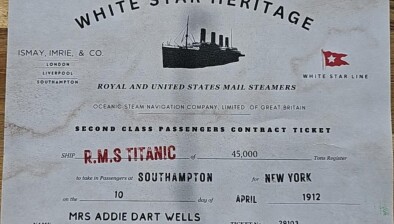

Upon arrival, I received a lifelike ‘boarding pass’ based on a real second-class passenger who had been aboard the ill-fated vessel: Miss Addie Darts Wells, who was travelling with her two children. As I walked past the displays, learning about the lives lost and the magnitude of the disaster, I felt quite emotional. There is something uniquely affecting about connecting with individual stories from such a monumental tragedy.

A boarding pass for Miss Addie Darts Wells from the Titanic Exhibition Wales.

I was struck by how much intellectual property (IP) played a role in the building of the Titanic. The exhibition not only honours those who perished but also celebrates the engineering achievements and subsequent safety innovations that emerged from the disaster. In our modern world of rapid technological advancement and continuous innovation, the Titanic reminds us that behind every patent and IP right, lies the potential to transform or even save lives.

From the manufacturing techniques of the massive anchor to the wireless communication systems that conveyed the SOS messages, these innovations tell a story of human ingenuity and ambition.

Designed to be unsinkable

Owners White Star Line launched the Titanic amid huge publicity for them and for the ship’s builders, Harland and Wolff, owned by Lord Pirrie, a friend of Bruce Ismay who was managing director of the White Star Line. The chief designer was Thomas Andrews, his son-in-law. This was to be the most innovative, most luxurious and one of the safest ships afloat, complete with modern ‘Allen’ dynamo generators driving electric heating, lighting, lifts and even hot baths. White Star claimed that Titanic was ‘designed’ to be ‘unsinkable’ due to its double-bottomed hull, which was divided into sixteen watertight compartments.

A patented anchor

The Titanic’s massive hand-forged centre anchor was the world’s largest at that time – over 18 feet long and weighing a massive 15 tons. Several companies needed to work together to create such an enormous piece. Each brought their own special knowledge and skills to the project.

A patent drawing for the Olympic class anchor.

The anchor’s design was secured under what is known as the 1910 Hall’s patent, which protected the innovative ‘Olympic Class’ anchor design. The innovation specifically addressed the critical weakness in stockless anchors (anchors without the traditional top crossbar), where the support bolts often bent or broke during deployment. The patented improvement achieved this by introducing special iron or steel blocks that transferred impact forces from shearing strain to compression. You can see the patent here.

Noah Hingley & Sons managed the overall project, while John Rogerson and Co. cast the anchor head according to the patented specifications. Walter Somers Ltd contributed their expertise in forging the massive anchor shank, using their specially developed techniques for working with huge pieces of metal.

The chains that would hold this massive anchor were proudly stamped as “Hingley’s Best” – an early example of trade mark use in manufacturing. This branding served two important purposes: it identified the source of the high-quality chains and protected Hingley’s reputation in the marketplace. Customers recognised this mark as a sign of quality and craftsmanship, much like modern trade marks help us identify trusted brands today.

This collaboration shows how even in the early 1900s, companies balanced sharing their expertise while carefully protecting their IP. Each contributor maintained control over their special knowledge while working together to create something no one could have achieved alone.

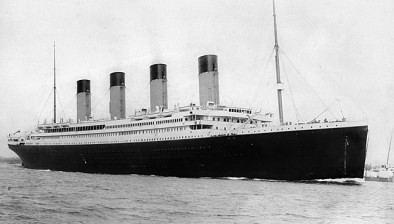

A model of RMS Titanic from the Titanic Exhibition Wales.

Wireless communication

Beyond the ship’s physical components, the Titanic’s tragedy is inextricably linked to Guglielmo Marconi’s wireless telegraph system. Marconi’s patented technology enabled the distress signals that brought rescue ships to survivors. His first patent in Italy in 1896 marked the beginning of a revolution in communication, culminating in the first transatlantic radio transmission in 1901 – an achievement that challenged existing scientific theories about radio wave propagation. View Marconi’s first UK patent for his wireless telegraph system here.

Marconi’s innovative work earned him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1909, shared with Karl Ferdinand Braun. The importance of his patent became painfully apparent during the Titanic disaster, where wireless communication played a crucial role in the rescue efforts, forever cementing its importance for maritime safety.

Legacy in intellectual property

The sinking of the Titanic catalysed an unprecedented wave of innovation in maritime safety and transformed safety regulations worldwide. According to the Comptroller of Patents, Designs and Trade marks report of 1913, the tragedy was followed by a number of inventions relating to saving life at sea.

A patent drawing of GB191226924A, Improvements in Apparatus for Raising, Lowering, and Stowing Ships Boats.

Inventors focused on improvements such as mechanical devices for the safe and swift lowering of lifeboats (GB191226924A), and detachable ship fittings that could serve as emergency rafts and buoyant personal wear. Others developed technologies to prevent similar disasters, including methods for detecting icebergs at night or in fog and improvements in apparatus for working watertight doors (GB191325407A). Particularly poignant were inventions ensuring wireless distress signals could be received even when operators were off duty – a direct response to one of the tragedy’s most heartbreaking missed opportunities, when nearby vessels failed to receive the Titanic’s distress calls.

Today, these innovations form an integral part of maritime IP which continues to evolve. Modern vessels today still benefit from the safety measures conceived in response to the tragedy, while contemporary patent filings build upon this foundation with advanced technologies that were unimaginable in 1912.

Preserving history through exhibition

In learning more about both the victims and the innovators connected to the Titanic, it brought home to me how IP serves not just commercial interests but also makes life better for us all. The wave of emotions I felt while holding Miss Addie Darts Wells’ boarding pass reflects this profound connection between human experience and technological progress – a legacy that continues to inspire seafaring innovation over a century later.

Christina Watts is a digital communications officer at the UK’s Intellectual Property Office (IPO). This article first appeared on the Intellectual Property Office blog.