Irish Legal Heritage: Criminal Conversation

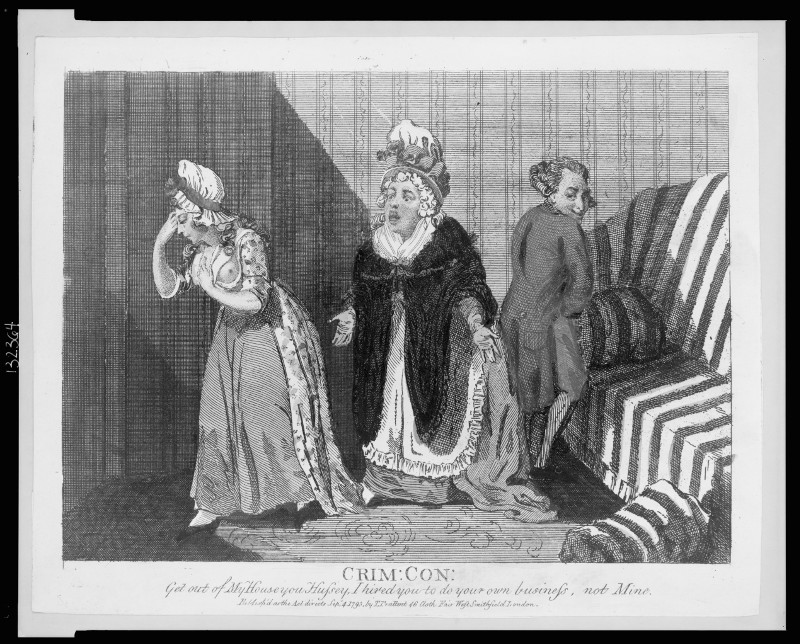

Cartoon showing a woman catching out her adulterous husband, and saying “Get out of my house you hussey, I hired you to do your own business, not mine”.

Criminal conversation gave a man a right of action for damages against anyone who had sexual relations with his wife, and the consent of the wife did not affect his entitlement to sue. It was not necessary that adultery resulted in separation, however if the couple was already separated the man was only entitled to sue if the separation was caused by the actions of the defendant. Despite the depiction in the picture above, it does not appear to have been the case that a wife could sue for criminal conversation in Ireland.

Enticement of a spouse to leave the other was also an actionable tort, which was independent of adultery. For example, the parents of a spouse had no right to entice their daughter away from her spouse – unless there was some evidence of her leaving through fear of bodily injury. Another actionable tort was that of harbouring a spouse after notice that a man’s wife left him without his consent. Again, this was independent of adultery and fear of bodily injury provided a defence.

It was not until 1981, under section 1 of the Family Law Act 1981 that criminal conversation, enticement, and harbouring a spouse was abolished in Ireland.

Criminal conversation developed as an action in trespass – based on view of wives being akin to chattel of their husbands. As such, the “injured” man was entitled to compensation for the loss he suffered – and was therefore based on the “value of the wife”. This value was calculated based on the pecuniary aspect, and the consortium aspect. Her pecuniary value was based on her assistance in the husbands business or in the home, and consortium was based on her ‘general qualities as a wife and a mother’. As a result, it was not uncommon for the plaintiff to describe his wife as a ‘beautiful, charming and engaging’ woman of great character to establish her high worth, and for the defendant to paint a picture of a promiscuous woman of low worth.

A famous trial for criminal conversion in Ireland was that of Sir John Piers, who was sued for having an affair with the wife of Valentine Browne Lawless, the second baron Cloncurry in 1806. The case is discussed in detail by Dr Niamh Howlin in Adultery in the Courts: Criminal Conversation in Ireland, where it is noted that the case was the subject of a poem by John Betjeman:

“The nobility laugh and are free from all worry,

Excepting the bride of the Baron Cloncurry.

But his lordship is gayer than ever before,

He laughs like the ripples that lap the lake shore,

Nor thinks that his bride has the slightest of fears,

Lest one of the guests be the Baronet Piers”

Seosamh Gráinséir