Irish Legal Heritage: Grounds for Divorce

By Samuel D. Ehrhart - An International High Noon Divorce (1906)

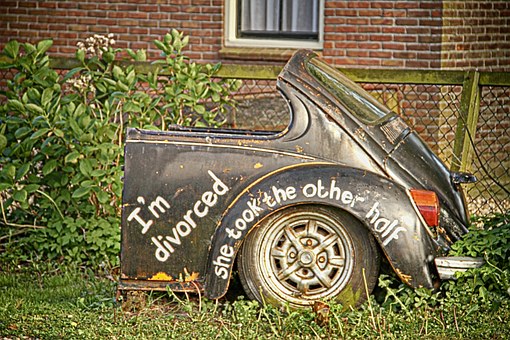

Brehon law, which was codified in the 7th and survived until 17th century, has been described in some instances as being moderately progressive in regards to women’s rights and issues like divorce. Given that divorce was prohibited in Ireland from 1937 until the marriage referendum in 1995, the numerous grounds for divorce recognised in ancient Ireland were comparably liberal to our more recent history.

It would be a stretch to say that women had equal rights to men, but wives were not treated as chattels. Marriage was a kind of contract in which the level of control asserted by husband or wife depended on the value of property each individual contributed to the union – for example, if the women had the lion’s share of property entering into the marriage, then she had more control, and her husband could not sell property without her permission. Wives were to be consulted on everything; even if they did not bring any property to the union, they were to be consulted before the husband sold any household necessities.

While husbands were allowed to hit their wives to “correct her”, if she was scarred by the punishment he inflicted, she was entitled to reparation or could divorce him. Additional grounds for divorce in Brehon law included infidelity; impotence; obesity; infanticide or attempted abortion; being indiscreet about your love life or spreading false stories; and theft. The prohibition of divorce in Ireland was driven by the church, and under British rule it was restricted to adultery. Under the Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Act 1857, a wife was only able to avail of a divorce from her philandering husband if his adultery was aggravated by further wrongdoings such as incest or bestiality.

After independence, Bunreacht na hÉireann prohibited divorce under Article 41.3.2º which stated that “no law shall be enacted providing for the grant of a dissolution of marriage”. You could say that the fifteenth amendment to the constitution in 1995 began restoring Ireland to its progressive roots.

Seosamh Gráinséir