Our Legal Heritage: Seán MacBride

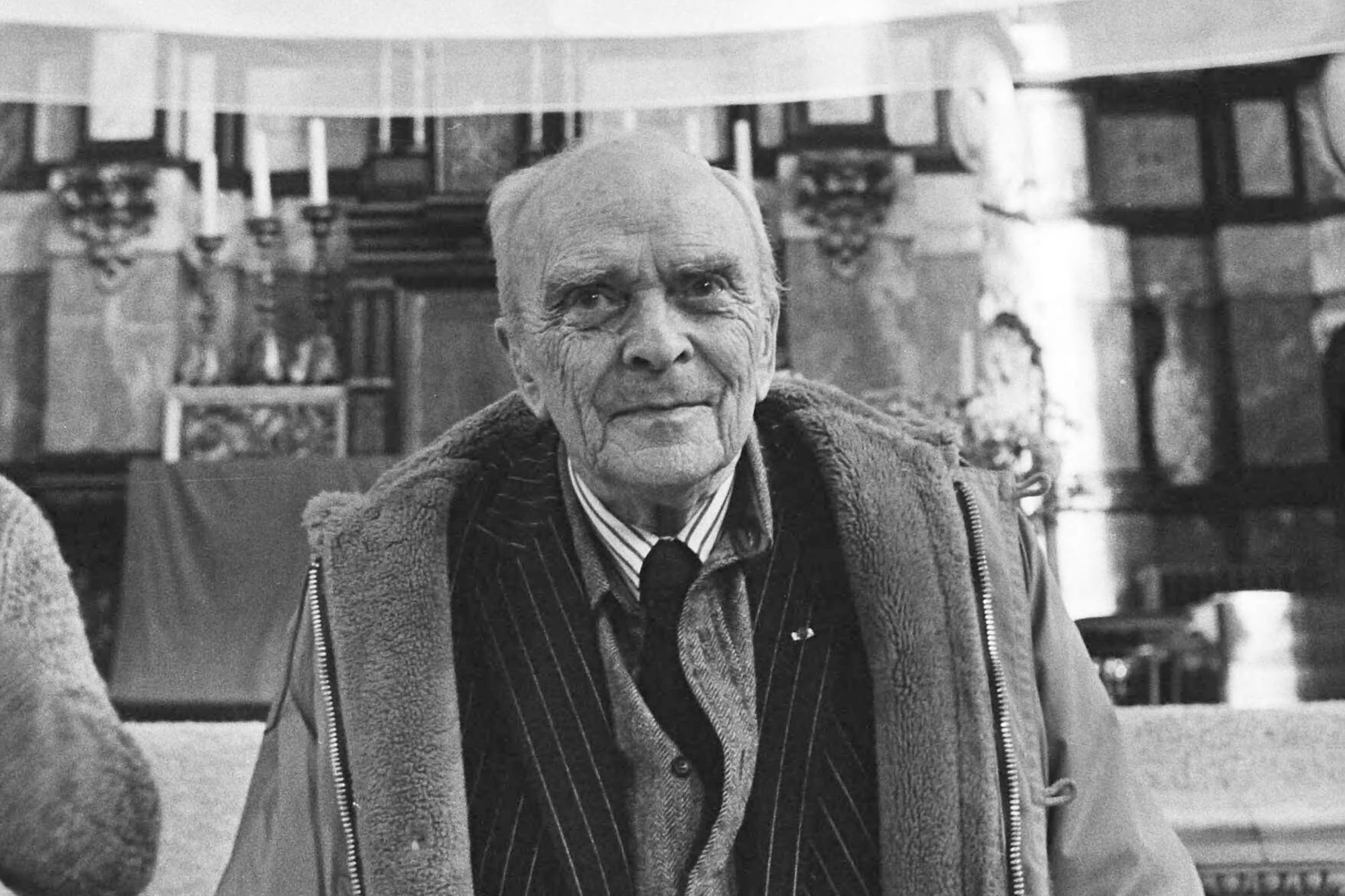

Pictured: Seán MacBride in October 1984.

Perhaps Ireland’s most famous — and unlikeliest — human rights activist, Seán MacBride was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize 50 years ago this week.

Born in 1904 to Maud Gonne, the actress, Irish republican icon and long-time muse of WB Yeats, and Major John MacBride, who was executed for his role in the Easter Rising, it’s little surprise that MacBride became a devout republican from an early age.

He not only lied about his age in order to fight in the Irish War of Independence as a teenager, but opposed the following Anglo-Irish Treaty and was among those taken prisoner after the surrender of the Four Courts garrison early in the Irish Civil War.

MacBride was evidently so attached to that building that, on his release in 1924, he resumed his study of law at University College Dublin and qualified as a barrister. He became a senior counsel in 1943, just six years after qualifying.

Though he remained involved in what was left of the IRA and briefly served as its chief of staff in the late 1930s, he eventually abandoned the paramilitary organisation and instead found his calling in electoral politics.

He succeeded in being elected to the Dáil in 1947 for his left-wing Clann na Poblachta party, and steered it into an initially uneasy coalition with Fine Gael that saw him serve as minister for external affairs from 1948 to 1951, shaping Irish foreign policy.

Thanks in large part to MacBride’s efforts, that government legislated to cement Ireland’s status as a republic through The Republic of Ireland Act 1948.

More importantly, that role raised MacBride’s international profile and gave him significant influence on the world stage, which was to last into his later life.

After losing his Dáil seat in 1957 and failing to reclaim it at the subsequent election, MacBride retired from politics and put his focus on the law and the budding world of international human rights activism.

In 1961, MacBride was a founding member of Amnesty International and joined its international executive committee, which he went on to chair for 14 years.

Two years later, in 1963, he played a key role in the founding of the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), which he was to lead as secretary-general for eight years.

He only stepped down from his leading role in Amnesty International to pay more attention to his role as UN high commissioner for Namibia from 1973 to 1977.

MacBride used his influence at the United Nations to press for world disarmament against the backdrop of the Cold War, opposing the proliferation of nuclear weapons.

In 1974, MacBride’s international efforts were recognised with the Nobel Peace Prize, which he shared with former Japanese prime minister Eisaku Satō.

Awarded for his “many years of effort to build up and protect human rights all over the world”, MacBride was the first of now five Irish people to ever receive the award.

He focused on disarmament in his Nobel lecture, saying: “The big powers are travelling on the dangerous road of armament. The signpost just ahead of us is ‘Oblivion’. Can the march on this road be stopped? Yes, if public opinion uses the power it now has.”

An editorial in The Irish Times welcomed the prize, saying of MacBride:

“As chairman of Amnesty International he has shown — what is not always the case with idealists — that he is aware of individuals, not only of people in the abstract. With his legal talents, he could easily have made a fortune at the Bar and relapsed into selfish, moneyed complacency; others are doing it all the time. Instead, he looked outward at the tormented world, and immersed himself in it.”

A year later, the Soviet Union also recognised MacBride with its International Lenin Peace Prize, making him one of very few people in history to receive both awards — another being Nelson Mandela.

The International Peace Bureau (IPB), which he served as president from 1974 to 1985, now awards a Seán MacBride Peace Prize every year to a person or organisation that has done outstanding work for disarmament or human rights.

Amnesty’s Irish headquarters continues to be known as Seán MacBride House.

In a decision which parallels the recognition of MacBride and Satō half a century ago, this year’s Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Nihon Hidankyo, a Japanese group representing nuclear disarmament campaigners and atomic bomb survivors.

MacBride’s incredible life serves as a powerful invitation to stand for peace — to “refuse to kill, to torture, or to participate in the preparation for the nuclear destruction of humanity”.