Review: The shocking crimes of baby murderer Lucy Letby laid bare

Robert Shiels reviews a new book on one of the most notorious crimes in recent English history.

The public must surely wish to have a comprehensive narrative of the course of conduct by a medically qualified person resulting in the deaths of many babies, and they have it with this book.

The shock of the whole scenario is not of a fanciful or unique set of circumstances, regrettably, as similar crimes are known to have occurred, but not on this scale.

The nature and extent of these crimes, however, means that the literature on the Lucy Letby case is likely to become a fairly crowded field.

It may be that the thriving industry of commentaries must be distressing for the families who lost children, and yet Facebook groups are not the only ones troubled by the verdicts on the many charges.

The joint authors of this study of the exceptionally sad circumstances assert that the “moral history of this story – the designation of villains and heroes is still being written”.

That refers obliquely to other members of staff at the hospital who ought to explain their inactivity in circumstances demanding attention, and to the subsequent inquiry now proceeding.

The need to catch and retain the interest of the reader is important in all the narratives of these real crime cases: catching is not difficult with notorious cases, but retaining is and the authors have succeeded in difficult circumstances.

Some readers may wilt with an opening account of the whole affair featuring a description of how it felt for the authors as journalists to watch the trial, although it was a marathon.

Thereafter, the narration of sustained inaction and the apparent initial policy of managerial containment rather than confronting the obviously suspicious circumstances is a tale of our times.

This explanation of the crimes and their medical technicalities and workplace contexts is informative, both as to what happened in the neonatal unit and generally in the medical background.

Deference ought to be given to the authors for their assessment of the trial, as they seem to have spent a great deal of time sitting through it and watching the witnesses and noting the evidence.

They saw and heard the crucial witnesses and speeches. That has assisted with explanations for the reader of the differing versions of the scientific evidence and is remarkably able.

Yet, given the very great subtleties of the case, it may have assisted to have had a note, in an appendix for example, of a complete list of the elements of the evidence that formed the basis of the Crown case. The points can be inferred from the narrative.

It would seem that in essence, first, proof of the crimes came from the adverse medical inferences drawn from the medical notes for the babies; the sudden and unexplained collapses medically of babies whose condition required monitoring because they were, for example, premature, but who were not necessarily ill as such.

The context is crucial: babies generally do not collapse unexpectedly, and if and when they do doctors are usually able to explain why that has happened, but these deaths and collapses not leading to death were unexpected and medically unexplained.

Secondly, proof of the accused Lucy Letby as the person responsible for the crimes was that only she was present at all the deaths of, or injury to, certain of the babies concerned.

That solitude often occurred at night when the staffing levels were low. When Letby moved to day shifts, comparable events occurred.

Letby called for assistance in some of the incidents and yet her demeanour was often one of apparent indifference which was inconsistent with a sudden and unexplained death of a child under her care.

Most importantly, a Post-it note found in Letby’s diary at home amounted to admissions against interest, regarded as confessions apparently to herself of responsibility for the killings.

The primary interest for criminal lawyers is highly likely to be the written words of Letby: “I killed them on purpose because I’m not good enough to care for them”, and also “I am a horrible evil person”.

The Post-it note is reproduced with the photographs in the book. There has never been any suggestion of these words having been dictated or written under duress. Letby’s contrary explanations of the true meanings of these writing given in evidence to the jury was, by implication, rejected by them as they held the charges as proved.

Another matter of interest to criminal lawyers (and of immense interest to the authors) is the failure to call a doctor to give evidence although present and advising the defence lawyers during the trial. That doctor was suitably qualified and prepared to challenge the inferences asserted by the Crown medical witnesses from the results of the medical histories of the deaths and injuries.

On the face of that possible defence evidence, it has been suggested that it might have been that a reasonable doubt for some, and perhaps many, of the charges could have been made out.

It has made clear that the decision not to call that doctor was one only for, and made, by Letby herself. The authors are left to speculate inconclusively about the reasons for that decision. It cannot be said that this is merely a book arguing for the innocence of Letby, as the authors are only too well aware of the conjunction of the admissions against interest, and the presence of and suspicious behaviour by Letby at highly significant incidents.

Moreover, some, but not all, of the critical incidents are supported by medical evidence of incontrovertible injuries due to criminal behaviour. In short, some incidents may have involved debatable science but the outcome of death or injury could only be the result of criminal behaviour.

This matter has not reached a procedural end as Letby has dispensed with her original lawyers and now has another to prepare submission to the Criminal Cases Review Commission.

There may require to be later editions of this book to cover developments, but in the meantime it is difficult to see how this intense narrative of the whole distressing course of events can be bettered.

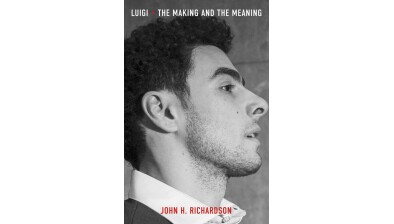

Unmasking Lucy Letby: The Untold Story of the Killer Nurse by Jonathan Coffey and Judith Moritz. Published by Orion, 426 pp, £20.