Irish Legal Heritage: Domestic Violence and Westropp’s Divorce Bill 1886

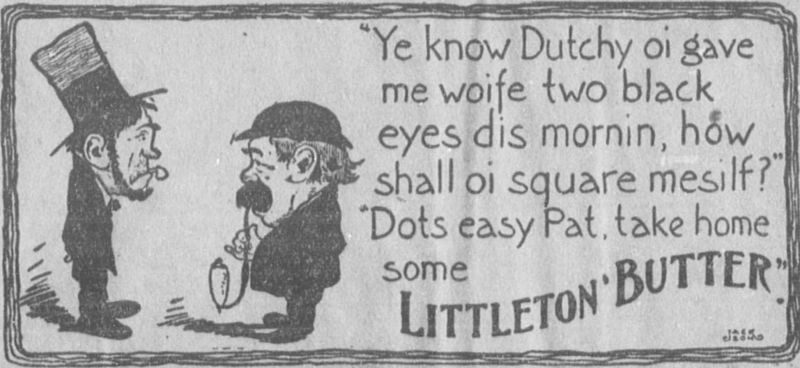

Pictured: Advertisement trivialising domestic violence in 1903

The commencement of the Domestic Violence Act 2018 brings significant changes to Ireland’s law on domestic violence, including the introduction of offences under the heading of coercive control, the court’s express consideration of the victim’s psychological and emotional welfare, and extension of the eligibility of Safety and Protection Orders to all partners in an intimate relationship.

Hailed by many as ground-breaking legislation, the history of legal remedies for victims of domestic violence in Ireland displays a pattern of resistance to reform. Indeed, it was not until the Family Law (Maintenance of Spouses and Children Act) 1976 that courts in Ireland could grant barring orders on the basis of spousal misconduct – notably prior to the constitutional prohibition of divorce being removed from Bunreacht na hÉireann after the 1995 marriage referendum.

Prior to independence, women in Ireland could be granted a divorce a mensa et thoro (i.e. legal separation, rather than a full divorce a vinculis) on the basis of “cruelty”. However, cruelty as a ground for divorce was famously difficult to prove, and the lack of protection offered to women and their children post-separation – and indeed the lack of women’s rights in general – meant that victims were reluctant to come forward. Domestic violence was largely seen as a legitimate form of punishment used by a husband to correct his wife, and so it was only in exceptional cases that the cruelty could be considered so bad as to be unacceptable. Indeed, as violence towards women began emerging as something for men to be “embarrassed” about, its impact was trivialised (as exemplified by the cartoon advertisement above).

Westropp’s Divorce Bill (1886) 11 App. Cas. 297 was a landmark divorce case in Ireland, in that it was the first ever presented by an Irishwoman, and it established a legal precedent “whereby any ground for divorce accepted by court could be applied in parliament”. The courts recognised both the physical and emotional abuse suffered by Louisa Westropp at the hands of her husband, who would spit in her face “by way of amusement” and was so violent towards her that she was “obliged to take refuge in a cupboard” late at night to avoid him. It was ruled that Louisa’s bodily fear fully justified her refusal to continue cohabiting with her husband, and that it was impossible for her to continue to do so with any reasonable prospect of maintaining her health (Urquhart, 2013). While the Westropp case was undoubtedly trailblazing for the divorce on the grounds of cruelty, it cannot be ignored that Louisa’s high social class as the granddaughter of the Earl of Mountcashel was a significant factor in her success – and indeed her ability to pursue separation in the first place.

The social divide in the ability of victims to separate from abusive intimate partners continues to this day, and in addition to physical, sexual, emotional, and psychological abuse – financial abuse has long been recognised as a form of coercive control, and it is hoped that the Domestic Violence Act 2018 presents an opportunity for strides to be taken on an issue wherein legal intervention has historically been left wanting.

Seosamh Gráinséir