Irish Legal Heritage: The ‘Long’ history of quackery

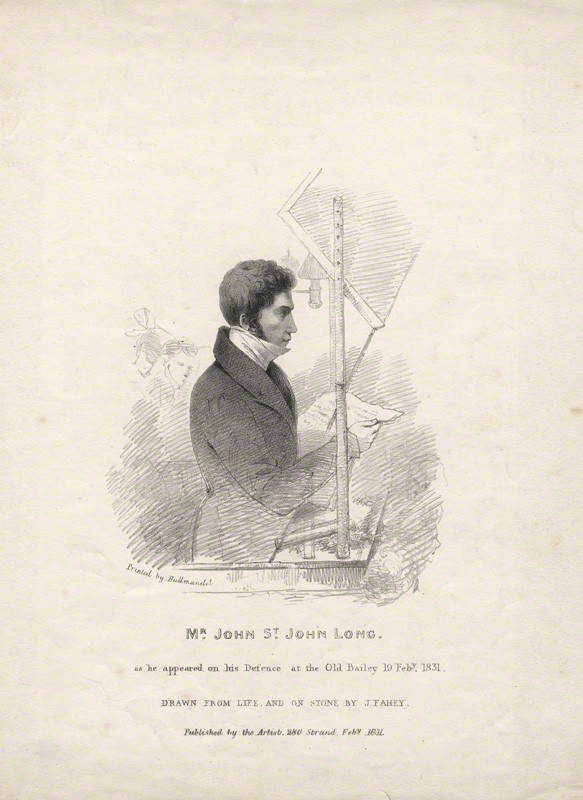

Sketch of John St. John Long at one of his manslaughter trials, dated 19 February 1831 (J Fahey, National Portrait Gallery)

Social media is replete with various examples of quackery; from detox teas and bee-sting facials, to more sinister bleach therapies and cancer cures. Far from being a novel issue, quackery in Ireland has a long history, and many of us who have grown up in rural areas have heard stories of people who you’d visit for ‘the cure’.

While leaving a banana skin on a wart isn’t going to cause you too much stress regardless of efficacy, there are opportunists who prey on some of the most vulnerable people in our society, offering expensive and unproven ‘cures’ for uncurable illnesses. Perhaps worse, ‘alternative therapies’ are often peddled to people with diseases which can be treated using conventional medical techniques.

In Brehon law, non-qualified medical practitioners “were subject to penalties if their treatment failed and they had not informed the patient of their irregular status” (J Fleetwood, ‘Irish Quacks and Quackery’ (1990) Dublin Historical Record). To plug the current gap in the law, in 2018, a private member’s Bill was introduced in the Dáil proposing new penalties for the “publication of any advertisement containing an offer to treat any person or provide any remedy for cancer, or any advice in connection with the treatment of cancer, or which suggests that a medical consultation, diagnosis, treatment or surgical operation is unnecessary for the treatment of cancer”; and this week the Health Products Regulatory Authority took action to block misleading advertisements which claimed to treat autism using stem cell therapy.

One of the most notorious Irish quack ‘doctors’ was John St. John Long, who was born in Newcastle, Co Limerick in 1798. He trained as an artist at the Royal Dublin Society School of Design, and worked as an art teacher in Limerick for a number of years before moving to London in 1822. Despite his lack of training, Long assumed the position of a ‘doctor’ and claimed to have a cure for tuberculosis (also known as ‘consumption’ at the time). Within a few months of opening his medical practice, Long was so successful that he moved to London’s Harley Street, adding prestige to his persona as a medical specialist.

Long’s cure for tuberculosis involved scrubbing the patient’s back or chest with a sponge soaked in a “secret formula” which turned out to be turpentine, vinegar, and egg yolk (S Hempel, ‘John St John Long: Quackery and Manslaughter’ (2014) The Lancet). The vigorous scrubbing of the patient’s skin, which occurred for up to ten days, would cause a weeping wound that would then be covered with cabbage leaves and left to heal. The weeping wound, he said, was evidence of the body ‘secreting’ the infectious disease.

It is evident from his first book, Discoveries in the Science and Art of Healing, that Long’s alternative therapies attracted criticism from the medical community. In addition to a string of “letters” from patients commending his treatment, the title page contained the following quote:

“Persons who object to a proposition, merely because it is new, or who endeavour to detract from the merit of the man, who first gives efficacy to a new idea, by demonstrating its usefulness and applicability, are foolish, unmanly, envious, and illiberal objectors; they are unworthy of the designation either of professional men, or of gentlemen”. (John St. John Long, Discoveries in the Science and Art of Healing (1830))

The same year his book was published, two of John St. John Long’s patients died – leading him to be tried for manslaughter. The manslaughter trials and Long’s final years will be explored in next week’s Irish Legal Heritage.