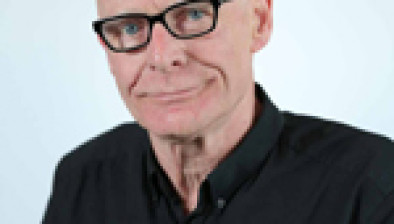

Lawyer of the Month: Gavin Booth

Credit: Mal McCann

This has been another eventful month for Gavin Booth. On Friday 7 October, a judge at the High Court in Belfast ruled that the PSNI was in breach of a legal duty to carry out an effective investigation into a fatal loyalist gun attack on a pub in Co Down 30 years ago, which involved allegations of collusion between police officers and the killers.

The verdict came in a legal challenge by Mr Booth’s client John McEvoy, a barman who narrowly avoided being killed himself in the shooting and developed post-traumatic stress disorder when a UVF gang attacked the Thierafurth Inn in Kilcoo during a darts tournament in November 1992 and killed Peter McCormack while seriously wounding three other men.

A Police Ombudsman’s report in 2016 had pointed to collusion between the security forces and the UVF operating in the South Down area at the time and the applicant believed that there was a link between the Kilcoo shooting and previous incidents, including the Loughinisland massacre in 1994.

It is the type of legacy matter that Mr Booth routinely deals with at Phoenix Law in Belfast, where he has been a solicitor for the past four years and specialises in actions against the police, public law and prison law.

It’s an uncompromisingly challenging area of the law which involves some of the most high-profile legacy cases emanating from the period we commonly refer to as “the Troubles”, including the RUC murder of Colum Marks in April 1991, the murder of Seamus Ludlow in County Louth in 1976, and the murders of Dwyane O’Donnell and Thomas Armstrong at Boyle’s Bar in Cappagh in March 1991 as well as the Kilcoo attack.

He has also appeared in both the Irish Supreme Court and the UK Supreme Court – in the latter in Re Anthony McIntyre [2019] which challenged the lawfulness of the controversial decision by the police to rely on tapes collected from the Boston College project.

“Essentially, what we at Phoenix Law are doing is dealing with these matters through the courts because there’s no other avenue open to legacy victims, many of whom have never been given any information about what has happened – let alone answers,” he says.

“One of the things that troubles our clients most is their sense of doubt that they can have faith in the Police Service of Northern Ireland to actually investigate these matters, when there’s a clear indication that this is something that they intend to leave for the future – and they have never actively sought to bring those suspects to court.”

One of Mr Booth’s current concerns is the proposed Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Bill, suggesting an effective amnesty for those accused of killing or maiming people during the Troubles – and which has recently been criticised for risking widespread breaches of human rights law by the UK Parliament’s Joint Committee on Human Rights.

Mr Booth says: “I’m worried that the bill will undermine the rule of law here. It will stop people having access to courts, stop them from having fresh inquests and shut down civil cases. So, if information comes to light in the future about a murder and people subsequently have no legal recourse, to me that’s an affront to justice.

“We should have the right to go before the court at all stages, and to me it’s an affront to justice as it doesn’t offer families any proper access to information while also being heavily weighted in favour of state actors.”

His practice – actions against the police, public law and prison law – means, he says, “exactly what it says on the tin” and he stresses that if someone has been wrongfully arrested or has experienced an incident involving the police, he is there to give them advice. “When it comes to prisons, I go in and meet with prisoners, represent them regarding prison issues and at certain times I take public law actions against the prison.”

He stresses: “We pride ourselves in being human rights lawyers, full stop. Our doors are open to anyone regardless of their creed, their politics or how wealthy they are.” He says people from all sides of the community come to the firm daily and adds that it also has a growing immigration practice.

It was clear from an early stage that Mr Booth, who took a solicitor trainee course at the Institute of Professional Legal Studies at QUB then an LLB with criminology and a Master’s degree in human rights law with transitional justice at Ulster University, was never going to be happy with a career in property, corporate or family law.

“I don’t think I would ever be content in the corporate world, representing banks or being involved in dealmaking. I live in Warrenpoint, in a border community, I’m from a working-class background and I think that helps me relate to most of the clients I represent,” he says.

He grew up, he adds, at a time and in a society that was witnessing much change. “People’s rights were a fundamental part of that – and a rights-based society is something which I’ve always proudly advocated.”

It’s a serious agenda and one that Mr Booth pursues energetically. He’s also a director of the Newry charity Davina’s Ark, which specialises in addiction and after care – and exercises enthusiastically at CrossFit.

“I go to a gym outside Newry – in fact I spend quite a lot of time there and find that it’s a very useful way of de-stressing. Since the Covid pandemic, I’ve also been walking in the Mournes quite often and nearly every Sunday I go out to Rostrevor and up and down the mountains.”

Some necessary tranquillity then in what is undoubtedly an exacting job and one that’s frequently subject to media attention. “Fortunately, it’s a very quiet life down here so while there’s a public person who goes to do his job there’s also another side to me that’s not as serious and is actually very relaxed.”

In the public job though, satisfaction comes from achieving results. “There’s a great sense of achievement when you can help someone like John McEvoy in the Thierafurth Inn case, who has waited 30 years for any form of justice or answers, or a win for someone in prison who no one else will stand up for and who has become lost in the system,” he says.

While he concedes that many people are still seeking answers, albeit years after the Good Friday Agreement and that there are significant societal problems prompted by factors such as recession, Brexit and the absence of a sitting assembly in Belfast, he remains hopeful about the path justice is taking.

“Since the beginning of my career, more people have been able to use the courts to vindicate their position, so overall, I’m optimistic about the future and in several ways we are moving forward. But people’s fundamental rights do have to be protected and the courts must be protected as a place that absolutely anyone can go to get justice.”