Mr Justice McMahon: Direct provision ‘much better than it was’

Mr Justice

Bryan McMahon

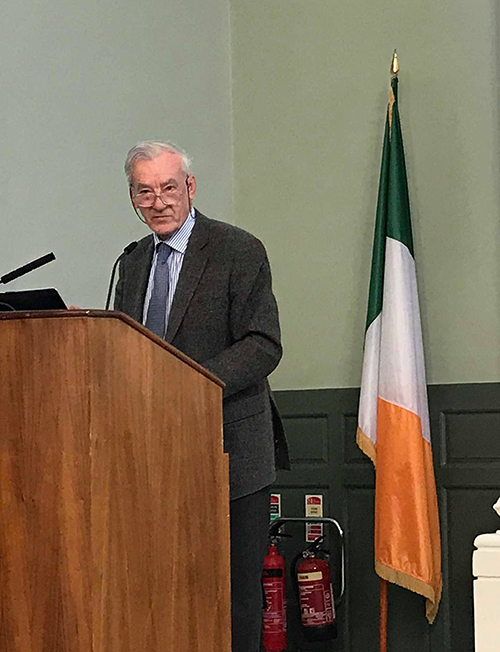

Former High Court judge Mr Justice Bryan McMahon, who chaired the working group on direct provision in 2015, has said that the system “may not be perfect, but it’s much better than it was”.

The retired judge made the remarks at the Law Society of Ireland’s annual human rights and equality conference at Blackhall Place on Saturday.

He said that direct provision was “a shambles” four years ago, and that despite “considerable progress”, significant work remains to fully implement the group’s recommendations.

Processing delays meant people were “languishing” for up to nine years waiting for a decision on their case, with 50 per cent in the system for more than five years.

The current number in direct provision stands at 7,500, with processing delays reduced to 14 months on average.

“If someone said to you you could stay in the Shelbourne Hotel for a week, you’d be delighted. If someone said you had to stay there for six years… you would go out of your mind,” he said.

“Some said to me, ‘I would prefer to be in prison because there’s certainty, I would be out in five years’, but in the limbo, there was no certainty and no future,” Mr Justice McMahon recalled.

“[It] was dreadful, to see these people walking around almost like ghosts, hollowed-out people who knew not where they were going or when it would end,” he said.

The conference

was held at

Blackhall Place

The right to work has made an “enormous” change, he said, but there are still obstacles, for instance applying for a driving license or opening a bank account.

Cooking facilities have been introduced nationwide on an “ad hoc” basis, but Mr Justice McMahon said it was to his “surprise and to the shame of the state” that none of the 11 centres operated by the government have such amenities.

However, he said it would not make sense to abolish the system, as it is difficult to see an alternative due to the housing situation in Ireland.

Referring to recent protests in Oughterard, Mr Justice McMahon stressed that communities must be consulted prior to the development of a centre in their area.

He estimated that 71 million people are on the move globally, and the conference was informed of the international developments for asylum seekers and migrants by Ambassador David Donoghue, special envoy for the UN Security Council Campaign.

The New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants and subsequent Global Compact frameworks have given further focus to human rights entitlements for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers and the responsibilities of nations to ensure these groups are treated with dignity and compassion.

“The key this is that a government like ours here must decide our policy towards asylum seekers or refugees or migrants within the framework of the global commitments it has entered into,” he said.

He said the government has been strongly committed in this regard, however, none of the documents go into detail about the nature or quality of accommodation for asylum seekers.

The conference brought together legal practitioners, policy-makers, academics and human rights organisations to discuss the international protection process in Ireland, as well as the progress made in the direct provision system.

Pictured (L-R): Shane McCarthy, chairperson of the Law Society's human rights and equality committee; Hilkka Becker, chairperson of the International Protection Appeals Tribunal; Mr Justice Bryan McMahon; Ambassador David Donoghue; Gráinne O'Hara; and Ellie Kisyombe

A mother who recently exited the system told the conference that residing in direct provision is “like living in an open prison” without knowing when you will be released.

Ellie Kisyombe, who was granted Irish citizenship last summer, said that while the system was set up ten years ago “in good faith”, the reality today is that children are growing up in “institutionalised environments” and people are suffering.

Ms Kisyombe, an activist and candidate for the Social Democrats in this year’s local elections, established Our Table in 2015 to highlight the lack of cooking facilities in direct provision.

“These families have never sat at dining tables and heard the tales of mothers or fathers from their countries,” she said.

Her struggles while raising two children as a single mother in direct provision are commonplace throughout the system. She said that an option for some mothers was to go into sex work to earn money to feed their children.

Ms Kisyombe also observed that some people “are being driven to mental health issues, anxiety, depression, even some of them reaching the extent of wanting to end their lives”.

“Living in direct provision is like living in an open prison…because you are not sure of the length of your sentence,” she said.

People in direct provision just want to have money to feed their kids, to cook their meals, and to have access to third-level education.

“We just want to be treated like any other human being,” she said.

Ireland is an intaker country for resettlement, explained Gráinne O’Hara, director of the division of international protection at the UNHRC.

92,400 people were resettled by the UNHRC in 2018 and this number is due to decrease this year as fewer countries are willing to resettle refugees, despite 37,000 people fleeing their homes daily.

“You would sometimes get the sense that everyone is banging down the door to get into Europe or the US but in fact, the statistics show a very different reality whereby 80 per cent of refugees globally live in countries immediately neighbouring where they originated from,” she said.

David Stanton, minister of state at the Department of Justice, was due to address the conference as a representative of the Government, but was unable to attend.