Review: The Power In The People: How We Can Change The World

This small book, with a big title, is commendable in several ways: it shows quite how many courts or tribunals and different types of case a member of the Bar, in the author’s generation at least, might have had to deal with.

The nature and extent of the pressing political and legal issues that are dependent ultimately on the knowledge and skill of the leader is remarkable. Solicitors are thanked throughout, although ultimately these cases were led by senior counsel.

The case load gives real insight as to how counsel and solicitors were, and still are, required to mediate the political and personal pressures inherent in public law business in order to be able to present the core issues properly, that is to say effectively.

Mr Mansfield defers properly to the personal responsibility of senior counsel leading in a capital punishment case by reference to a miscarriage of justice from Cardiff in the early 1950s, but that should not detract from recognition of the gravity of the litigation and therefore the personal responsibility that he has carried over the decades.

Similarly, the book contains some, but to a disappointing extent not much, advice on the art of advocacy. The difference in the legal demands of tribunals and criminal trials, and coroners’ inquests and other forms of inquiry are dealt with as they arise but more explicit explanations would certainly inform those learning to become court practitioners. The author’s experience of major complex inquiries in the press and public gaze is such that he might have explained more of the difficulties in dealing with practical pressure groups with legitimate complaints whose sheer numbers make for professional sensitivity to avoid conflicts of interest, even if it is possible to obtain clear instructions.

It may be that “people power is unstoppable” but litigation is not, or at least ought not to be, a public rant and should be directed at some objective, and attaining that end is difficult.

With counsel apparently committed personally to some of the political and social issues under review, it would have been interesting to have had advice on how to separate properly any subjective influences from the need for objective propositions and submissions.

The blurb on the book includes a quote from the author to the effect that he wishes to inspire people, give them a blueprint for fighting their own battles, and challenge the status quo. This appears then to be a non-party political manifesto for unity and strength for an unspecified group of the public.

There is a stated limit to the assertions by the author that “we are always stronger”. The difficulty there is that attempts at reforms of, for example, the traditional criminal procedure can vary and improvements produce reaction from those who purport to be radicals.

A juryless court would lead to an independent judiciary drafting statement of facts, and an explanation of the reason for the findings of the court. Many criminal trials now conclude with no obvious reason for the jury having reached a particular decision.

What then are the limits of the status quo that the author says are to be challenged? In an age of nationalism there may be those who think that a miscarriage of justice in Cardiff (which features heavily) ought to be dealt with in there as a separate jurisdiction. If the justification is the application there of English law then the issue begs another question.

Others in Northern Ireland may question the inherent acceptability of senior counsel at the English bar appearing in Belfast (when not apparently qualified in that jurisdiction) and engaging in litigation there, or, alternatively, based on activities there but heard in England for security reasons. The “trappings of colonial rule” noted by the author come in many forms.

Moreover, and this is put as delicately as possible, the call to arms of “the people” to challenge what is mentioned at one point in regard to the police as “the basic intransigence of entrenched power”, might be thought to apply to other aspects of the legal system and the profession.

If there is a need to challenge the organisation of the law process that appears to have been left to “the people” to fight for. The call to arms in this book avoids, it seems, the very places on which the complaints are often founded.

There was clearly a real empathy, for the nearest relatives of the deceased in their helplessness in the face of bureaucratic anonymity, felt by the author in representation of them in the many and very contentious tribunals, coroners’ inquiries and criminal trials.

For others, the book is an interesting manifesto for something, but that final entity remains unstated, or at least hovers around the politicians standard fallback position of “a fairer society”.

There is latent in Mr Mansfield’s descriptions a manual on advocacy for law students, perhaps given his extensive professional experience he ought to be encouraged to direct his attention to that.

In the meantime, this modestly priced book is recommended for the broader almost ideological questions the learned author raises for general consideration, an approach perhaps informed by his earlier studies for a degree in philosophy.

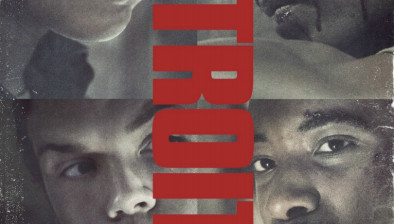

The Power In The People: How We Can Change The World by Michael Mansfield KC